From the Executive Editor

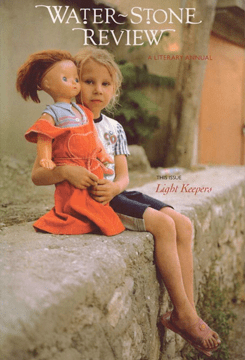

Light Keepers (v. 8)

Light Keepers, our title for this year’s issue, is inspired by Stephanie Dickinson’s luminous story, “Q & A.” This is what Dalloway, the youthful narrator, says after visiting a lighthouse on the Jersey shore with her father: “I wish I could have been a light keeper.”

Light Keepers, our title for this year’s issue, is inspired by Stephanie Dickinson’s luminous story, “Q & A.” This is what Dalloway, the youthful narrator, says after visiting a lighthouse on the Jersey shore with her father: “I wish I could have been a light keeper.”

“You are my light keeper,” Daddy says, his hair blowing skyward. “You’re the light of my life.”

Dalloway and her father are soul mates. They have a quirky, symbiotic relationship. He is a good dad. But he’s engrossed in his own sexual identity crisis, and in the course of the day he puts Dalloway at risk. His failure, or inability, to protect her is a theme that reverberates throughout this year’s issue.

The authors in this volume are preoccupied with such failures, mostly on the part of parents and other adults responsible for the well-being of young people. In his memoir, “The Past is Present: A Memoir of a Father/Son Reunion,” Alexs Pate laments the decision that he (and other African American fathers) made earlier in his life to abandon his children. The narrator in Robert Ready’s “Autocephalous” mourns the death of his daughter in the tragedy of September 11. The parents in “And We Sell Apples ‘77” leave their children with a friend so they can spend the afternoon at a local bar. The list continues.

Dalloway is one of a multitude of light keepers who people the poems, stories, and essays in this issue. Individuals whose desire is to love us, to hunt for beauty, to care for nature, to honor language’s power to change the world. Lori Stoltz introduces another kind of light keeper when she asks Maxine Hong Kingston: “As the oldest of six children in the Hong family, are you the designated keeper and recorder of stories?” Kingston replies: “The keeper of family stories is not ‘designated,’ not elected, not chosen. One just takes on the role, and she remembers and tells those stories whether the family likes it or not.”

Language, of course, has always lighted the way. In his review of Mark Conway’s Any Holy City, Stan Sanvel Rubin writes, “Are poems really written only to communicate? Or is it possible that at the heart of some, a secret fire burns . . . . Call it a desire for language to matter as much as desire itself.”

Another focus for the authors in this issue is a terrible violence at home and abroad. “Old hatreds,” says a character in “Autocephalous.” These old hatreds show up between Christians and Muslims, Irish Catholics and British Protestants, Greeks and Turks. There are suicide bombers in Iraq, graves in Estonia, Taiwanese protestors killed by troops from China.

Destructive events and actions across the globe – against humans, against animals, against nature – create a pressing need for light keepers, in whatever guise we can find them.

We are happy to publish the winners of this year’s Jane Kenyon Poetry Prize, judged by Elizabeth Alexander: “Yau Yellow,” by Su Smallen; “What Kwahada Means,” by Teresa Whitman; and “I Speak in My Mother’s Voice,” by Susan Terrill.

The Meridel Le Sueur Essay, “A Bridge of Bones,” is an elegaic lyric essay written by Terry Tempest Williams in honor of her brother, Stephen Tempest Williams, who died in January, 2005, of cancer.

Our three writers’ interviews are with Mary Ruefle, author of eight books of poetry; Maxine Hong Kingston, author of The Woman Warrior: Memoirs of a Girlhood Among Ghosts and China Men, among others; and Pete Hautman, winner of the 2004 National Book Award for Young People’s Literature for his novel, Godless.

Two years ago we published a piece of work from each of the MCAD/Jerome Foundation Fellowships for Emerging Artists recipients and we are happy to be doing so again. (MORE HERE.)

On their walk along the beach, Dalloway and her father (“Q & A”) pass over a railroad track littered with dead monarch butterflies. “I ask Daddy for his windbreaker and he gives it to me and I fill one of its pockets with butterflies. I would like to live in a world of butterflies, and, since birds slaughter butterflies, there would be no birds in that world . . . . I put on Daddy’s windbreaker and keep my right hand in the butterfly pocket. I imagine them reawakening, licking my fingers, becoming an evening glove.”

I, too, want a world of butterflies, and I applaud Dalloway’s desire to protect them. But I also want the birds. I want Eva Hooker’s great gray owl (“Great Gray”) who hears whispers under ice and keeps watch. I want Alison Hawthorne Deming’s doltish doves and fearless thrashers. Her gila woodpeckers, cactus wrens, and ravens (“Woman”).

And I want the secret fire burning at the heart of poetry – burning at the heart of these pages of Water~Stone Review.